''Biplane Rides: Free. Landings: $40.'' That's the sign by the grass runway of the Old Rhinebeck Aerodrome, a shrine to early aviation tucked away on 110 bucolic acres in Dutchess County, N.Y. ''Come Josephine in My Flying Machine'' drifts from the loudspeakers as four passengers don leather helmets, mount the wing of a roaring 1929 open-cockpit New Standard biplane and slip onto the wooden bench seats.

The body of the aircraft is wood and steel tubing covered in fabric. The only navigational instrument is a compass. The ticket-booth attendant, in a costume Myrna Loy would envy, shouts, ''Don't lean out.''

The pilot taxis, the wheels lift from the earth, and the meticulously restored black and orange antique plane climbs to 1,200 feet, soaring over a quilt of rambling farms, winding roads and velvety green lawns.

With no cabin walls to intrude, cool air rushes by, colors leap out and views are unobstructed in nearly every direction. Swimming pools glisten like jewels; a dip of the wing reveals the Hudson River unspooling north through rolling hills. After 15 thrilling minutes, which make Amelia Earhart a kindred spirit and a pilot's license as desirable as breathing, a swooping turn delivers the plane over the treetops and back to the tiny airfield. (Longer rides, to a variety of destinations, are available on weekdays.)

Mike Lawrence, 51, one of the pilots, says he has seen more smiles than white knuckles from his passengers. ''We give you the helmet and some goggles,'' he said. ''But you're responsible for picking the bugs out of your teeth.''

But even without going up for a spin in a vintage airplane, a visitor can have a day of fun at the Old Rhinebeck Aerodrome. On weekends, antique planes take to the sky in gloriously corny and daring air shows -- valentines to the stunt-flying barnstormers of the early 1900's. Four museum buildings hold one of the largest collections of antique planes in the world -- about 55 models dating from 1898 to 1935 -- along with vintage cars, bicycles and motorcycles.

Among the planes are an exquisite working reproduction of a 1910 Hanriot (look for a giant origami dragonfly) and an original 1909 Voisin (like a box kite with a wingspan of nearly 33 feet). One of the motorcycles is a cherry-red Indian, built in 1917.

The Old Rhinebeck Aerodrome, a nonprofit organization, was created by Cole Palen, an airplane buff and former mechanic who died 12 years ago. In 1951, he spent his life savings on six World War I airplanes auctioned by the Roosevelt Aviation School on Long Island and stored them in his family's vacant chicken coops. (The school and the Roosevelt Field airstrip, where Charles Lindbergh began his flight across the Atlantic, were later razed to build the Roosevelt Field shopping mall.)

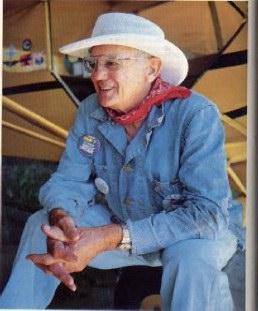

Eight years later, Mr. Palen, part visionary, part showman, bought the abandoned farm that is now the aerodrome, cleared a runway and began giving loosely organized flying demonstrations. (''I never met a bigger ham,'' Jim Hare, 45, the current air show announcer, said with a laugh.) Gradually, Mr. Palen expanded his fleet and developed the aerial acts.

At the shows, Mr. Hare weaves jokes dating to the Wright Brothers into his educational patter. When a pilot in a Tiger Moth, a biplane built in 1944, swooped through the sky to cut a rapidly unraveling roll of toilet paper with his propeller, visitors learned that the white scarves pilots once favored were used to wipe away castor oil -- the engine lubricant of choice -- splattered on flight goggles by rotary engines. The Tiger Moth, Mr. Hare said, ''can turn on a dime and give you 9 cents change.''

People in the audience, who sit on planks propped on cinder blocks, are recruited for a vintage fashion parade in which they wear outfits like a purple satin one-piece flying suit in the style favored by Harriet Quimby, the first American woman to get a pilot's license.

On Saturdays, the show focuses on the pioneering years, when a plane in the sky was a shocking sight. Sunday shows feature aircraft from World War I and characters like Pierre Loop de Loop and Madame Fifi, whose French accents are as shaky and entertaining as the plot. Children hiss at the Black Baron of Rhinebeck (Mr. Palen's signature role) and cheer for Trudy Truelove, and everyone breaks into spontaneous applause when the oldest flying airplane in the country, a 1909 Bleriot, the first type of plane to cross the English Channel, lifts a few feet off the runway.

AS he bought his planes, Mr. Palen also collected a coterie of cronies besotted with early aviation and recruited them to fly in his shows. Some still do. Others are a fund of memories. Bill Poythress, 85, who can be found in the newly renovated model museum amid dozens of delicate model airplanes, met Howard Hughes in 1938, when Hughes stopped at Floyd Bennett Field in Brooklyn on his around-the-world flight. ''He was a real nice person, and a snappy dresser,'' said Mr. Poythress, who has volunteered at the aerodrome for 46 years. ''He stepped out of that plane like he was leaving the St. Regis.''

Mr. Poythress is enthusiastic about the flying skills on display at the aerodrome. ''You don't see pilots this talented everywhere,'' he said. ''They land so gently, the grass doesn't even complain.''

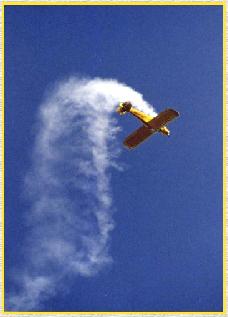

The shows inspire flights of fancy. One Sunday in June, a man in worn overalls wandered onto the grass runway during the show, took a 58-year-old egg-yolk yellow Piper Cub in what appeared to be a theft and careened full throttle into the sky. ''Folks, that's the farmer from across the way,'' Mr. Hare said, his voice suggesting panic. ''He's never flown solo.'' The ''farmer'' spun the plane like a top, rolled 360 degrees (an impossible feat for a Piper Cub, according to the owner's manual), looped the loop three times, flew sideways, cut the motor and glided back to earth, unscathed, to stop at the precise spot where he had left his straw hat.

Small children in the audience gasped; everyone else, from gearheads to grandmothers, grinned. The interloper was revealed to be Stanley Segalla, 80, also known as the Flying Farmer, a self-taught pilot who has performed aerial acrobatics at the aerodrome since its inception. Mr. Segalla, whose wife, Sue, 67, flies him to work from Connecticut, attributes his vigor to the salutary effects of his work. ''The blood's always rushing back and forth from my head,'' he said. ''That keeps my cholesterol down.''

The pilots pose for pictures with fans after every performance. ''I meet people who saw me fly 40 years ago, and now they're bringing their kids,'' Mr. Segalla said. ''That's the best part of my job.'' He is proud of the aerodrome's record. ''In 46 years, we've never had a serious injury,'' he said.

In his act, Mr. Segalla illustrates how planes can glide to earth if the engine loses power; last Sunday, in a rare accident, a reproduction 1915 Nieuport 11 lost power and the pilot, Brian Coughlin, 40, made an unscheduled and rough forced landing far from the crowd. Mr. Coughlin broke his leg, but his colleagues expect him to be flying again as soon as he can climb back into a cockpit. ''We face some of the same dangers as the early aviators,'' Mr. Lawrence said, ''but it doesn't stop us.''

According to Mr. Segalla, who spends winters in Florida teaching aerial acrobatics, the aerodrome, with its intimate atmosphere, gives audiences a rare, visceral appreciation for early flight. ''You smell the castor oil. You hear the engines. Where else is a kid going to see these old planes in action and get the itch to fly?''

Love, also, seems to thrive at the aerodrome. Mr. Hare, the announcer, met his wife in 1982 when she

signed up to play Madame Fifi. Two couples have married during the biplane rides and six couples have become engaged. Mr.

Lawrence, who is quick to point out that all the highflying unions are intact, proposed to his own girlfriend while piloting

the noisy biplane. ''I passed her a note,'' he said. ''She nodded yes. I guess I spelled everything right.''

FLIGHT

PLAN

The Heritage Of the Skies